Discipline in Schools

Effective teaching and learning depend on a positive school climate. Reducing the need for disciplinary actions in school is a goal for all educators.

"Each LEA shall ensure that schools promote a positive climate with emphasis on mutual respect, self‐control, good attendance, order and organization, and proper security. Each LEA shall develop protocols that define a set of discipline strategies and constructs that ensure that students and adults make positive behavioral choices and that are conducive to a safe and nurturing environment that promotes academic success." - Basic Education Program, Section G‐14‐2.1.4

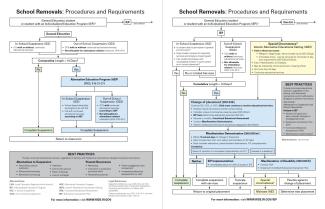

School Removals - Procedures and Requirements

RIDE has developed a flow chart to remind school leaders of the Procedures and Requirements related to student suspensions. This document should be shared with all school leaders, especially those involved in school discipline. It is important to remember the differing requirements for students in special education and those in general education. The document includes a flow chart for each, along with legal references and best practice suggestions.

Suspension Data

Any time a student is removed for disciplinary reasons for one day or more, it must be reported to RIDE. RIDE reports these to the U.S. Department of Education.

Every disciplinary record includes information on who the student was, what the nature of the infraction was, whether a weapon was involved, if someone was physically injured, the duration of the suspension, and whether it was an in-school suspension, out-of-school suspension, or an Interim Alternative Educational Setting (a special circumstance under special education law).

RIDE does not collect information on detentions, community service, or other types of disciplinary actions.

Guidance and data specifications on the discipline data collection can be found on the Data Collection page.

A law passed in 2016 (S2168 as amended/H7056 as amended) requires districts to analyze their discipline data each year to determine whether there are disparities in the rates of suspension for students based on their race, ethnicity or disability status. If there is a disparity, the district must submit a report to the council on elementary and secondary education with details and corrective actions to address the disparity.

Districts are encouraged to make use of resources on the InfoWorks website, including the Advanced Reports on suspensions. In addition, in determining whether differences in rates should be deemed disproportionate, districts should consider the following parameters:

- Minimum n-size – In order to ensure meaningful results, there must be sufficient numbers in a subgroup for a comparison to be done. For federally mandated special education disproportionality calculations, RIDE uses an n-size of 10 in the numerator (i.e. there must be at least 10 incidents of suspension in a subgroup for it to be evaluated). Please note that a much less strict standard is used for data to be displayed in InfoWorks, which uses a minimum n-size of 10 in the denominator (i.e. there must be at least 10 enrolled students in the subgroup).

- Comparison group – In assessing disparities, suspension rates for a particular subgroup could be compared to rates for all other students, for all students, or for another specific subgroup of students. Given the racial diversity in the state, RIDE uses all other students for its special education disproportionality calculations. Using the all students’ rate is simpler, if less precise.

- Risk Ratio – When comparing rates for different subgroups, some variation is to be expected. The risk ratio determines what threshold of variation would constitute disproportionality. Many legal consent decrees use a ratio of 2:1 as the threshold. RIDE uses a risk ratio of 2.5:1 as the threshold in its special education disproportionality calculations.

Although it was written for a different purpose, more information on these decisions can be found in this guide from the IDEA Data Center (IDC).

In the event that a district determines that there is a disparity, per the law, corrective actions to address the disparity should be developed after consulting with representatives of faculty and prepare a report for submission to the Council on Elementary and Secondary Education. In developing corrective actions, please review the information below on prevention and alternatives to suspension. In addition, the IDC’s Success Gaps Toolkit has resources to help a district conduct a root cause analysis and make a plan for reducing disparities.

Problems with Out-of-school Suspension

Suspending and keeping students out of school may seem to administrators to be an appropriate response to discipline issues but is not always meted out equitably and often creates new problems without really solving the behavior problem.

Out-of-school suspension continues to be a frequently used response to disciplinary infractions. During the 2015-16 school year, the total number of out-of-school suspensions was 11,736. This represents a 52% drop over the previous 5 years, from 24,685 in 2010-11.

RI Department of Education 2015-16 data show:

- There were fewer out-of-school suspensions than in-school suspensions in Rhode Island during the 2015-2016 school year (11,736 vs. 12,744, respectively). Prior to the 2014-15 school year, there were more out-of-school suspensions than in-school suspensions every year.

- 9462 individuals – or almost 7% of the student population – was suspended at least once, either in-school or out-of-school.

- Of all in-school or out-of-school suspensions, 2085 or 9% involved elementary school students, 9924 or 41% involved middle school students, and 12,471 or 51% involved high school students (Note: totals do not add to 100% due to rounding).

Of great concern is the disproportionality in the rates of suspension for minority students.

- In Rhode Island during the 2015-16 school year, minority students made up 41% of the student population, but received 54% of all in-school and out-of-school suspensions (13,113 out of 24,480).

- Students with disabilities also are more likely than other students to be suspended. While 16% of Rhode Island students were in special education in 2015-2016, they accounted for 30% (6948) of the suspensions and 26% (2,503) of all students disciplined.

To learn more about suspension rates in RI or specific districts, go to ReportCard.ride.ri.gov, select the state, a district, or a school, and click on its "Civil Rights Data" tab.

Teachers, administrators and parents understand the importance of consistent school attendance. Students cannot learn if they are not in class. Absenteeism, for any reason, is one of the strongest predictors of course failure and students dropping out-of-school, which is why it is a key indicator in many Early Warning Systems. Out-of-school suspension is contradictory to all of those policies and efforts to have students attend school.

- For more information on the importance of attendance, go to the National Center for School Engagement

- Everyone Graduates and Attendance Works are other websites that span the prek-12 issues of absenteeism with strategies to encourage school attendance.

- Learn about RIDE’s Early Warning System (Guide or Fact Sheet)

When a child receiving special education services is suspended from school for more than 10 school days (cumulative) in a school year, it is considered a change of placement. (300.536) The child must continue to receive educational services to enable him or her to participate in the general education curriculum and progress toward IEP goals, though services may be in another setting. In addition, the child must receive a functional behavioral assessment along with behavioral intervention services and supports designed to address the behavior violation so it does not recur. A manifestation determination meeting must also take place. (300.530d) In addition, RIDE, along with all other states, must report to the US Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) the number of districts that have a significant discrepancy in the number of students receiving special education services that are suspended more than 10 days compared to general education students. This is also broken down by race/ethnicity and reported to OSEP.

Research shows that out-of-school suspension generally does not improve behavior, and can actually be harmful to students resulting in increased disengagement, lower academic scores and increases the risk of a student dropping out. Numerous reports cite the prevalence and problems with school suspensions. Out-of-school suspension means students are home, often alone with no supervision. The message to them is that they are not wanted nor welcome at school, increasing their level of disengagement. Many students see an out-of-school suspension as a “vacation”, rather than a punishment. These students miss out on academic instruction, and if they are already behind in their academics, it becomes even more difficult for them to get caught up when they return.

The disparity among subgroups according to race, gender, disability status and English language learners being removed from the classroom is also clear and well-documented. Federal laws prohibit discrimination in discipline policies and practices based on race, disability, religion, and sex.

For more information see:

- “Out-of-school and Off Track: The Overuse of Suspensions in American Middle and High Schools,” Center for Civil Rights Remedies (April 8, 2013)

- “Blacklisted: Racial Bias in School Suspensions in Rhode Island,” American Civil Liberties Union of Rhode Island (June 2013)

- “Dear Colleague” letter – guidance on how to identify, avoid, and remedy discriminatory discipline – (January 8, 2014) U.S. Dept. of Justice (Civil Rights Division) & U.S. Department of Education (Office for Civil Rights)

It is important that proper discipline is maintained in order for schools to establish “and promote a positive climate with emphasis on mutual respect, self-control, good attendance, order and organization, and proper security” as required in the Rhode Island Basic Education Plan (RI BEP). The RI BEP goes on to say that “each LEA shall… define a set of discipline strategies… that ensure that students and adults make positive behavioral choices and that are conducive to a safe and nurturing environment that promotes academic success.” (G14-2.1.4)

Appropriate and effective discipline is designed to provide instruction to students intended to reduce the problem behavior. Schools must consider discipline as part of educational process and ensure their practices:

- Allow students to accept responsibility for their actions

- Place importance on the value of academic participation and achievement

- Build positive self-image

- Teach students alternative methods of dealing with problems (Beverly H. Johns & Valerie G. Carr, 2012)

School disciplinary measures should not be used to exclude students from school or otherwise deprive them of an education. Out of school suspension should be used as a last resort in schools in order to preserve the safety of students and staff.(Addressing the Out of School Suspension Crisis: A Policy Guide for School Board Members, 2013)

Prevention of Suspension

The best way to reduce out-of-school suspensions is to implement strategies that prevent the behavior issues from ever taking place. Below are some practices focused on preventing behavioral problems from occurring or being repeated and so can reduce the need for suspension.

Schools and districts should review and revise their policies and codes of conduct to ensure that out-of-school suspension is only used for the most serious infractions and only when truly necessary. Policies should reflect an approach designed to be constructive and instructive, keeping students in school and engaged in learning, rather than an approach that is primarily punitive. For many disengaged youth, getting suspended may simply reinforce their behavior and make any reengagement with school less likely.” (Losen & Martinez, 2013)

Administrators should be on the lookout for policies that unintentionally discriminate against certain groups. Policies may appear to be written in a neutral manner, but may not be administered in the same fashion for all students. Are there policies and practices that tend to target certain infractions that are typically committed more frequently by a particular group?

- For more information on identifying, avoiding and remediating discriminatory practices, please see guidance at “Dear Colleague” letter – guidance on how to identify, avoid, and remedy discriminatory discipline – (January 8, 2014) U.S. Dept. of Justice (Civil Rights Division) & U.S. Department of Education (Office for Civil Rights)

Schools should analyze their suspension data to identify causes, patterns, and subsequent supports, interventions or training. Schools typically collect detailed information regarding disciplinary infractions, especially those resulting in suspension. By analyzing this data, patterns can be identified related to:

- Types of infractions

- Times that infractions occur

- Areas/Locations where infractions take place (cafeteria, playground, certain classes)

- Disproportionality trends (such as special education, race, gender)

- Patterns for a particular child

- Patterns for a particular teacher

After identifying patterns, a problem-solving team or administrator(s) may be able to identify appropriate strategies to prevent the problems from re-occurring. If problems consistently occur with certain teachers, more training in classroom management and de-escalation may be needed. Disciplinary infractions and referrals may be concentrated in certain locations or times of day which may decrease with higher levels of supervision or changes of activities. Data may show that one type of infraction is more common than others which may lead to a plan to target that particular problem and address the issue on a school-wide or classroom basis.

Some infractions, such as insubordination, may be interpreted differently ways by various people resulting in varying consequences for students committing similar infractions. Some infractions may need to be defined more specifically. If the data shows students of certain cultures or ethnic backgrounds are consistently being reported, staff may benefit from training to identify cultural differences, and how to respect those differences while teaching children about the culture and expectations of the school environment. Analysis may also show that certain individuals or certain groups tend to receive lesser punishments, such as a phone call to parents or detention, while others receive harsher punishments, such as suspension, for similar infractions. Data may also show that problems are occurring consistently with a small group of students, which may point to a need for specific interventions targeted at that group of students. (Dufresne, Hillman, Carson, & Kramer, 2010)

Behavioral data, including suspension information is a key indicator of Early Warning Systems to identify students at risk. Other components of an Early Warning System include academic performance and attendance. Although out-of-school suspension may be considered an ‘excused absence’, it is still a day out-of-school.

- For more information see the Rhode Island Early Warning System Guide and EWS Factsheet. It should be noted that the Early Warning System is only effective if data is entered into the system on a daily basis.

- For information and tools that are available nationally, go to the National High School Center's EWS Guide

A focus on building relationships and a sense of community in the classroom can provide a foundation to prevent conflict and wrongdoing. These are informal and formal processes that precede wrongdoing, but help everyone to work as a community and understand ‘we are all in this together’. By building relationships and the sense of community, students and teachers develop a greater understanding and empathy for each other. The use of these restorative practices has been shown to reliably reduce misbehavior, bullying, violence and crime among students and improve the overall climate for learning. (Wachtel, 2012) Establishing this strong foundation of community sets the stage for the use of restorative justice when a conflict does take place. When a misbehavior occurs, the impact on the community (e.g. classroom or school) is discussed, which leads to discussion on how to repair the harm done.

For more information, go to:

Providing direct instruction in social and emotional skills, with opportunities to role play and practice in various settings, can help students learn the social, relationship and behavioral skills required to meet school and societal expectations. This direct instruction can be provided to small groups of identified students can be incorporated into everyone’s class schedule on a school-wide basis. The Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) has identified five interrelated sets of competencies:

- Self-awareness

- Self-management

- Social awareness

- Relationship skills

- Responsible decision-making

Children who have participated in SEL programs have significantly better school attendance records, less disruptive classroom behavior, like school more, and perform better in school and are less likely to be suspended or otherwise disciplined. The SEL programs with the best outcomes are multi-year in duration, use interactive rather than purely knowledge-based instructional methods, and are integrated into the life of the school rather than being implemented as marginal add-ons.” (CASEL, Safe and Sound, 2005)

The CASEL Guide rates and identifies well-designed, evidence-based social and emotional learning programs. In addition, the Guide shares best practices for district and school teams on how to select and implement social and emotional learning programs.

For more information, go to

Positive relations are one of the most important protective factors for children at risk of disciplinary trouble, academic failure, and dropping out. A mentor can be a teacher, community member, or another student. Mentors can provide a student with emotional support and positive feedback, which can improve their engagement, behavior and achievement in school. (Dufresne, Hillman, Carson, & Kramer, 2010)

Mentoring programs can be formal, with structured times, meetings and activities; or informal, with an adult periodically checking in with the student. Communication can be in person, through email, texting, or phone. This simple low-cost, low-tech strategy can have powerful results.

“Expected individual or school results include:

- Improved school achievement;

- Increased graduation rates;

- Increase in self-esteem;

- Increased school attendance;

- Decrease in discipline referrals;

The Commonwealth Fund's survey (McLearn, Colasanto, and Schoen, 1998) reported the following:

- 52% of students skipped less school;

- 48% of students improved their grades;

- 49% of students got into less trouble in school;

- 45% of students reduced their substance abuse”

This information and more can be found at

A model, called Collaborative & Proactive Solutions, (formerly Collaborative Problem Solving), has been developed by Dr. Ross Green based on the idea that behavioral issues stem from a lack of skills. The model begins with identifying the expectations the child has difficulty meeting and the conditions under which the difficulty occurs. It is not focused specifically on the behavior (hitting, screaming, talking), but on the difficulty the child has in meeting certain expectations under specific conditions. The next step is to talk to the child and to elicit information from the child regarding those situations. Dr. Greene has developed suggestions on how to talk to a child so the conversation is meaningful and honest, truly reflecting the child's feelings and thoughts. Next, the adult expresses their concerns. Finally, there is collaborative discussion where the adult and child brainstorm to find a solution that addresses the problem that is satisfactory to both. This method is non-punitive and non-adversarial, focused on helping the child improve his skills in the area of difficulty.

For more information go to

Functional behavioral assessment is an approach to diagnose causes and identify likely interventions to address problem behaviors.

Functional behavioral assessment involves identifying the function, or purpose, the behavior serves and then using that information to identify interventions that will meet that need in an appropriate way. Usually, the function, or cause, of a student’s behavior is due to a need to get or avoid something (such as attention of teacher or students, a certain activity or task) or due to a physical need such as sleep, food, etc. biological, social, affective, and environmental factors that initiate, sustain, or end the behavior in question.

Through an FBA, attempts are made to meet the function of the behavior in appropriate ways. For example, a student may have a need for attention from teachers or peers and may be meeting that need by talking out. Through an FBA, a plan can be developed so that need is met by providing more attention for positive reasons. (The Center for Effective Collaboration and Practice, 1998)

Online training modules regarding Functional Behavioral Assessments can be found at

Establishing positive, respectful and trusting relationships with parents is important. It is especially important that both schools and parents work together to provide the best supports for students. With open communication and trust, both schools and families feel safer in sharing information, including information that may be sensitive. It is important that families feel students will be supported and not simply punished when information is shared. The opinions and ideas from family members must be respected and valued. School staff need to make the effort to truly hear what families say and understand their culture. This can help everyone have a clear picture of the child, their environment, their stressors, and expectations, in order to identify the best strategies to address issues.

For more information, go to:

Data shows that a much greater proportion of African American and Hispanic students are suspended as compared to white students. Many of the infractions are for offenses that subjective in nature, such as Disrespect/Insubordination or Disorderly Conduct. When different cultures meet, there is a good chance that what is accepted as a norm in one culture is different than expectations and what is accepted in another. Training for staff can address this. It is important for staff to understand what cultural traits can be addressed through instruction and when staff may need to make adjustments in their teaching style.

Some resources for schools and districts can be found at

Data may show that certain teachers refer students to the office more than others. Analysis of the referrals may show a need for training in basic, core, classroom management skills. Data may point to particular problem areas for certain teachers which can be addressed through professional development or mentoring with another teacher or administrator. Establishing classroom rules and routines, and consistency in responding to problems related to those rules can prevent many problems from escalating. Teachers may need training in specific de-escalation techniques or learn new strategies to deal with particular students or specific issues.

The National Center for Intensive Interventions provides an approach known as data-based individualization (DBI) for students needing intensive, (Tier 3) interventions. According to their website, “DBI uses data to individualize instruction, increase engagement, and provide opportunities to practice new skills. Data-based individualization is a systematic approach to intensive intervention. It is an iterative, multi-step process that involves:

- Collecting frequent (usually weekly) progress monitoring data;

- Analyzing that data according to standard decision rules to determine when an increase to the student’s goal is needed (in the case of strong progress) or a revision to the intervention program is needed (in the case of inadequate progress;

- Introducing a change to the intervention program when progress is inadequate, which is designed to improve the rate of learning; and

- Continuing to use Steps 1–3 on an ongoing basis to develop an individualized program that meets the student’s needs.”

A number of resources, tools, and ideas are available at

Behavioral issues often stem, at least in part, from academic difficulties. When students do not understand the material or do not have the skills needed to do well, they may feel frustrated or ashamed, resulting in acting out behavior, cutting class or truancy. Providing appropriate academic interventions and supports can improve students’ academic achievement and engagement, which can result in improved behavior.

For more information, go to

- The National Center for Intensive Interventions provides information, tools and resources to provide academic interventions in addition to addressing behavioral interventions.

A behavioral contract is a clear, understandable, written agreement with one or two clearly stated positive goal(s) between staff members/parents and a student. The goal(s) may be short-term or long-term, and should be measurable with clearly defined criteria for success. The level of reward and consequences should match the student's interests and perceived difficulty of the task, as well as be readily available when the conditions of the contract are met.

Alternatives to Out-of-School Suspensions

Consequences that keep students in school while holding them accountable for their actions may be more meaningful and have a greater impact on students without interrupting their educational services.

One advantage of after-school, before-school, lunch or Saturday detentions is that students do not miss class time or valuable instruction. Detention can provide an opportunity for students to complete school work, and for schools to provide positive behavioral supports to help students review their behavior and identify better choices for the future. (See Part 4 In-School Suspension) For students, this consequence may have a more of a negative perception and impact than out-of-school suspension since detention is served on a student’s ‘own’ time. (Dufresne, Hillman, Carson, & Kramer, 2010, p. 23)

Restorative justice is based on respect, responsibility, relationship-building and relationship-repairing. It aims to keep kids in school and to create a safe environment where learning can flourish.

If a student misbehaves and a restorative justice system is in place, the offending student is given the chance through a mediation process to make things right. Students learn the impact of their actions and how it affects others, and parties try to come to agreement on consequences that are fair and respectful and not solely punitive. (Delporto, 2013)

Restorative practices can prevent both contact with the juvenile justice system and school suspensions. Restorative justice also holds the potential for victims and their families to have a direct voice in determining just outcomes, and reestablishes the role of the community in supporting all parties affected by misbehavior or crime. Several restorative models have been shown to reduce recidivism and, when embraced as a larger-scale solution to wrongdoing, can minimize the social and fiscal costs of crime. (National Council on Crime and Delinquency, 2013)

For more information, go to

- Youth Restoration Project (local initiative)

- We are Teachers - "Restorative Justice: A Different Approach to Discipline"

- "Restorative Practices in Schools: Research Reveals Power of Restorative Approach" from the International Institute for Restorative Practices (IIRP)

- SaferSanerSchools (project of IIRP)

- Oakland Unified School District Restorative Justice

Students may be asked to reflect and analyze the situation and the problem behavior. This may take place with a counselor, mediator, or teacher to assist the student in identifying the problem, discuss what happened, why it was a problem, what other options were available, and what they might do differently in the future. With the help of an adult, students may be able to identify some appropriate strategies they can use when similar situations occur in the future. Some students may be able to work through this on their own, while other students may need assistance.

Working with parents is vital in addressing student behavioral concerns. Out-of-school suspension is sometimes seen as a way of catching the parents’ attention, but can also be a way of alienating and turning parents against the school. If it is a hardship for parents when a student is suspended, or if they disagree with suspension as an appropriate consequence, it changes the parent-school relationship to one of negativity and distrust. Schools must be genuinely open and truly respect parent concerns. (Dufresne, Hillman, Carson, & Kramer, 2010, p. 26)

Parents and schools should be working together to identify successful strategies to help students improve academically, behaviorally and socially. A sense of trust must be established so parents feel comfortable sharing sensitive information about their child with school staff. Parents know their children well, usually better than the school staff. Parents may have insight to causes of inappropriate behavior or have ideas for consequences and schools should be open to their ideas. Schools must be prepared to refer parents to appropriate community resources when issues extend beyond the capacity of the school support system.

Service to the community, either the school community or the greater out-of-school community can be an alternative to out-of-school suspension. These services assignments may be cleaning up in school or school grounds, or other jobs around the school building. (Dufresne, Hillman, Carson, & Kramer, 2010) Community service, which may be seen as a punitive consequence by students, allows them to contribute to the greater good, and can be a learning experience for students.

A consequence for behavioral infractions can be loss of privileges. The privileges may relate to participating in extracurricular activities, sports, or school events. Care should be taken, however, when prohibiting students from participating in activities in which they have a high interest. For some students, these extracurricular activities are a major factor in keeping them engaged in school. Not allowing students to attend or participate in these highly motivating activities can result in less interest in school overall, and lead to dropping out.

In-School Suspensions

Recognizing the negatives effects of keeping students out of school, many districts are establishing In-School Suspension programs. It is important to remember this is still a suspension and removes students from their classroom, although some educational services may be provided.

RIDE defines in-school suspension in a fairly broad manner as a:

“temporary removal of a student from the regular classroom for disciplinary purposes, during which time the student remains under the direct supervision of, and in the same physical location as, school personnel. In-school suspension may occur in a separate classroom or a separate building and, in some instances, may occur outside of regular school hours, so long as state requirements for length of the school day are met. Typically, the student is required to complete course work during this time. The student may receive academic instruction, behavioral intervention services, counseling or therapeutic services.”

RIDE recognizes that many districts are implementing programs with supportive, instructive, therapeutic and unique components when students are removed from class due to disciplinary infractions, but these still fall into the category of in-school suspensions.

One big advantage of in-school suspension programs is that it keeps students in school. Students are removed from their usual classes, but are in a supervised program as compared to out-of-school suspension where they are home, often unsupervised, and away from instruction and the learning environment.

However, an in-school suspension is still a removal from a student’s regular class. Although students may be given work to complete from their class, and a content-area instructor may be available, this is still not the same as being in class. Students in in-school suspension miss out on class discussions and often do not participate in any hands-on projects or lab work. For students receiving special education, in-school suspension is a removal from the environment specified by their IEP team.

When establishing an in-school suspension program, school leaders should consider the purpose and goals of the program. Is the goal of the in-school suspension program to prevent future behavioral problems? Is it to help students catch up or stay current with academic instruction and assignments? Is the program trying to provide a counseling or therapeutic component to help the student behave differently in the future? Simply punishing a student and having them “do their time” will not necessarily prevent future occurrences.

There are three main models of in-school suspension programs (Morris & Howard, 2003):

- punitive,

- academic, and

- therapeutic.

Typically, most schools offer a combination of approaches. Although removal from class may be seen by many as a punitive consequence for a disciplinary infraction, it also provides an opportunity for schools to provide academic instruction, behavioral intervention services, and counseling and/or therapeutic supports. Ideally, the student should be able to work with someone to discuss the incident that was problematic, identify the inappropriate behavior, the impact of that behavior, and other alternatives to prevent or act differently in the future. Some programs require students to complete a ‘reflection paper’ as part of the in school suspension program.

In-school suspension programs allow schools to have some flexibility in how the day is structured for students. Schools may choose to allow students to leave the program in order to attend a lab class or other activity that cannot be completed in the in-school suspension classroom. Services for students with disabilities can be provided by allowing the student to attend certain classes or arranging for the special education teacher to go to the in-school suspension program for part of the day. Simply sending students to an in-school suspension room for one or more days does not address the root cause of the problem.

Review your data for in-school suspensions in a manner similar to data review for out-of-school suspensions. Look for patterns in the data. Is there a particular racial or ethnic category that is receiving a disproportionately higher number of suspensions or a higher number of suspensions for similar infractions? Are certain teachers making a larger number of referrals than others?

For students that are ‘repeat offenders’, analyze their individual data further – are there patterns as to the type of infraction, or the time or location where the infraction occurs. Does the student need additional interventions? Would a referral to the RTI Team or Evaluation Team be appropriate? Would an FBA provide information as to the function of the behavior and possible changes that could be made to prevent future occurrences?

Just as districts try to minimize the need for out-of-school suspension, they must have a similar philosophy toward in-school suspension. It is important to remember that each student is unique, coming from different situations, cultures, values and backgrounds. No one strategy will work for all students. It is important for schools to connect with students and their families and work together to help each student be as successful as possible.

- 2015 Rhode Island KIDS COUNT Factbook. Indicator 68 Suspensions. (2015) Rhode Island KIDS COUNT.

- Beverly H. Johns & Valerie G. Carr . (2012). Reduction of School Violence: Alternatives to Suspension. Palm Beach Gardens: LRP Publications.

- Addressing the Out-of-school Suspension Crisis: A Policy Guide for School Board Members. (2013, April ). National School Board Association

- Losen, D. J., & Martinez, T. E. (2013). Out-of-school & Off Track: The Overuse of Suspensions in American Middle and High Schools. The Civil Rights Project.

- The Center for Effective Collaboration and Practice. (1998, January 16). Why a Functional Behavioral Assessment is Important.

- Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) (n.d.). What is Social and Emotional Learning?

- Wachtel, T. (2012). What is Restorative Practices? International Institute for Restorative Practices

- OSEP Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (n.d.). SWPBIS for Beginners

- Delporto, D. (2013). Restorative Justice: A Different Appraoch to Discipline. We are Teachers.

- Dufresne, A., Hillman, A., Carson, C., & Kramer, T. (2010). Teaching Discipline: A Toolkit for Educators on Positive Alternatives to Out-Of-School Suspension. Hartford: Connecticut Voices for Children.

- National Dropout Prevention Center/Network (n.d.). Mentoring/Tutoring

- Nasrat, D. (2013). What Is - and Is Not - Restorative Justice? National Council on Crime and Delinquency.

- Wright, D. B. (2008). Restraint and Seclusion: Time-Away: A Procedure to Keep Task-Avoiding Students Under Instructional Control. PENT Positive Environments, Network of Trainers, CA Dept. of Ed. Diagnostic Center, Southern CA.